Connection is life - Alone Australia episode 5

Duane Byrnes may have left lutruwita, but his gift remains.

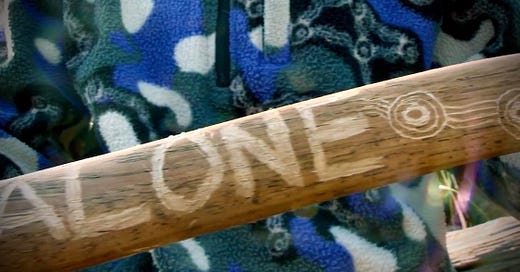

Duane, one of Alone Australia’s First Nations contestants, left his solo wilderness experience with a profound understanding that to survive in the wilderness, he needed people. In his final scenes he revealed a stunning art piece he had carved on his hatchet. As participants, we weren’t allowed to take anything away from lutruwita, so he brought lutruwita with him as he left, not only in his heart, but as a healing story.

Stylised fish and birds soar through the wood. Swooping arcs of hill and water capture the essence of country. Concentric circles depict the campfires of his ancestors and family, connected by wavy lines, leading to the word ALONE in large capitals. On the other side, those circles and lines pick up again. In an instinctive, heartfelt weaving, he transforms the solitude of his sojourn into something beautiful, but deeper than that, he uses art to heal himself. He wove his mob into his journey and himself back to his mob.

It’s easy to look at the Alone Australia experience from a viewpoint of logic and reason, and if we do this, we come unstuck.

As participants, we very quickly discover that logic does not hold sway against wild nature. Nature has no true straight lines. Imposing them does not tend to go well. How do we explain a lake? Can we ever perfectly make meaning of a tree? Science takes us so far but only scratches the surface of available variables. What remains is… mystery.

What if a ‘tree’ is not a thing, but a process of infinite generosity? Home for birds. Catcher of wind. Giver of oxygen. Safety for small creatures. Singer of water songs. Resources for shelter. Fuel for fire. Delight for the human gaze. We could say more accurately that it is ‘treeing’. Attempting to nail it down reduces its staggering glory to dry concepts, holding us away from comprehending the everchanging miracle of its existence.

It also keeps us small.

By stretching our awareness to encompass the monumental grandeur of treeing, we stretch our minds to also allow the wonder of a living planet to become part of our daily experience, as our ancestors did.

For 350 000 years, give or take, humans have been homo sapiens. For 340 000 of those years, we were hunter gatherers, living in dynamic relationship with wild nature for survival, travelling in small bands, gathering nutrition from the landscape, following resources as they ebbed and flowed with seasons. Wisdom was handed down through story, song and dance, ritual and ceremony. Connection with each other, with place and with spirit was the tapestry through which all experience was threaded.

Over millenia we adapted to questions of survival by using our big brains to solve problems in the moment, a million tiny choices that led us away from small mobile hunter gatherer bands living in harmony with existing resources, to the security of stored calories centred around towns and cities, managed by complex hierarchical societal structures of have and have-not, until we ended up with a culture that prioritises productivity over connection.

Somehow, along the way, we disconnected from the song of our planet, our home. And really, how’s that working for us?

In the wilderness, very quickly, we see it doesn’t. Work, that is.

In Alone, humans are thrown into a solo survival situation where habitual ways of modern thinking come up against the unpredictability of life. Theories of cause and effect give way to the real-time Mandelbrot equations described by James Gleick in his book Chaos. In the wilderness we see the infinite fractal edges of existence unfurling, where everything is connected to everything else, and a butterfly flapping its wings on the mainland means a fish swims right past the bait in lutruwita.

One simple truth of wilderness survival is that humans are not designed to live alone. We are mammals, and mammals need touch. Our skin is hairless and fragile, without a warm pelt to protect us. Our claws are nonexistent, our fangs cannot penetrate a hide. These big beautiful brains have come at a cost. We need each other, we need to work together to keep our species alive. This is as true now as it was 350 000 years ago.

We tune into a TV show that challenges this idea because on some atavistic, instinctive level, we understand that sane solo survival is largely impossible.

This wisdom is most apparent in Alone’s First Nations contestants, who come from extant lineages stretching back tens of thousands of years. Aboriginal Australians evolved a culture of literally singing to, and being sung by, the land. Such deep listening that no decision is taken without first conferring along all the strands of connection, because trees aren’t things, they’re family, and just like your sister, they get a say.

Alone is designed to provide entertainment, and as such is largely viewed through a modern lens of rationality. We have been culturally trained along paths of linear, outcome-based thinking and we judge the cast accordingly.

For us, though, out there in the mud, it’s something else entirely. Prize money quickly becomes irrelevant when participants are broken open by nature. Strategies and plans fall apart under a breathless expanse of stars. Limited calories result in altered brain function. Our experience stops being about outcome and shifts into process. Viewers are confused by the apparent foolishness of participants’ often seemingly bizarre choices and thought processes.

Tree becomes treeing. Human becomes humaning. Doing dissolves into being. Participants connect with a way of life our hunter gatherer ancestors knew, but in an environment denuded by modern human practices, with scant food sources, in harsh winter conditions. We must survive without the supporting cultural structures of community, social technologies, ceremony, art, lore, law, and connection-centred practices that evolved over hundreds of thousands of years. All at once, modern humans run into the gaping holes where logic doesn't reach. What transpires is a conversation between the heart of the human and the heart of the land, and that conversation is deeply personal and ultimately inarguable.

When Duane carves his story into the handle of his axe, he’s gifting us a tiny insight into deeper truths, ones our hunter gatherer ancestors knew as purely as breathing.

Without mob, it’s hard for survival to make any sense at all. Life cannot be tamed by logic. And art makes the journey worth it.

Check out Duane’s art on Insta @jarlinaart

Follow Gina on Insta @gigiamazonia

Painting by Duane Byrnes @jarlinaart

I shall now look at all the trees and think that they are treeing, and this shall make me happy.

When I went through a time of high anxiety, I moved to my now-home amongst trees and looking at the calm waters of the Walpole Inlet in WA.

Each time I had a worry thought, I would look at the trees, and say to myself - They aren’t bothered - as the swayed in a gentle breeze, held the birds and shed the odd leaf.

It always returned me to a sense of their steadiness and firm groundedness, deep in the earth.

Trees have been, and still are, healing me every day!